王明明,壬辰年生于北京,籍属山东蓬莱。其年少怀艺,志趣高远,然庚戌年,年十七,适逢国家风云突变,明明被遣为工铣者,日操金刀,锻铁铸器,双臂劳倦,筋骨困顿,然其志未泯,每于工隙间,携画夹行于郊野,观山川之胜,揣天地之灵,运笔描摹,遂积日月,技艺大成。十载在厂,王明明常心系丹青,不辍习研。于戊辰年间,忽觉艺途迷茫,遂转思古代题材,潜心研习,探中华文化之源流,欲从中寻得真谛,遂得道悟:中原画道,当循古训,继承而创新,方可自立于艺林。

丁巳年,师周思聪荐之,得入北京画院,拜名师,学众艺。人物、山水、花鸟,书法各有所成,然风格多杂,难辨其宗。遂沉思虑,欲脱旧而创新,探传统与现代之融合,立艺途新峰。庚申年,作《杜甫》一画,以杜工部《春望》为题,创历史人物画,施古法,运新意,借电影之蒙太奇,置人物群像于背景,诗意与画境相融,风格日益见长。辛酉年,复作《招魂》,描屈原于汨罗江畔,烟气缥缈,人物隐现,诗情画意更深。

然风云骤变,改革之潮席卷中华,西风东渐,传统画法受冲击,诸画家皆困惑。癸亥年,明明游历法兰西,见西洋画艺,惊叹于心,然归国后,愈感中原画道,须循己路,不可随波逐流。遂愈加笃定,探传统之精髓,融现代之思维,创诗意画,彰显其对中华文化之深悟。自乙丑年至己巳年间,明明遍游名山大川,览万卷书,游历感悟,尽展笔端,融古人之情于当代之景。己巳年,始创一套册页,表其数十年之思索,融诗意于画境,终得风格独立,技艺臻于纯熟。戊戌年,明明接待欧陆诸博物馆长,展中原丹青之作,齐白石等人之画,令欧人叹为观止。明明深感中原画道之独特,须保其精髓,守其根本。中华文化,源远流长,唯有深研古训,融入时代,方能立于不败之地。

纵览王明明之艺,其承新朝而复古风,人物、花鸟、山水与书法,无不贯清旷精和之旨。其作初观,清旷之气扑面,脱俗而不染尘,涵盖万象,既见广学多识,又显高瞻远瞩与卓然自立。细品则精和之韵悠然,精者,尽善尽美,无应时之俗,映其性格之谨严;和者,中正平稳,藏其胸怀之浩然与理想之炽烈。归而言之,王氏之艺,直达其心迹本真,使中国画于其笔下复归古道,既修身养性,又抒情达意,于斯,以艺养心,借画观世,身心俱得其乐。

观王明明之画,得“能”而近“逸”。古来文士雅崇“逸品”,鄙“能品”于末流,视“逸”为天授,不假雕琢。然今之世,风气已异,若仅持“逸”以示人,恐举步维艰。况今之知“逸”者,寥若晨星。“逸笔草草,不求形似”,固为“逸品”一途,然鲁迅所讥之笔触,未必皆入“逸”之境。今人审美,重“能”而不弃“逸”,然其义已有所嬗变,求能者非匠,雅而近逸,尤为世所推崇。

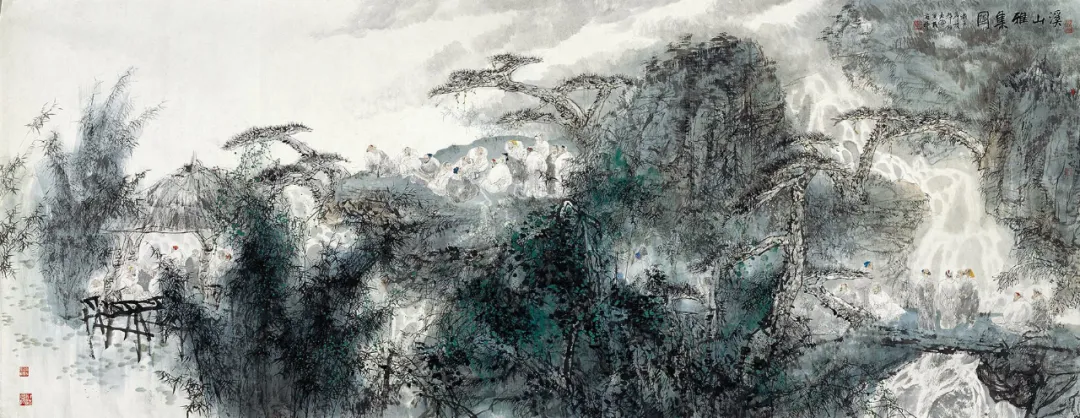

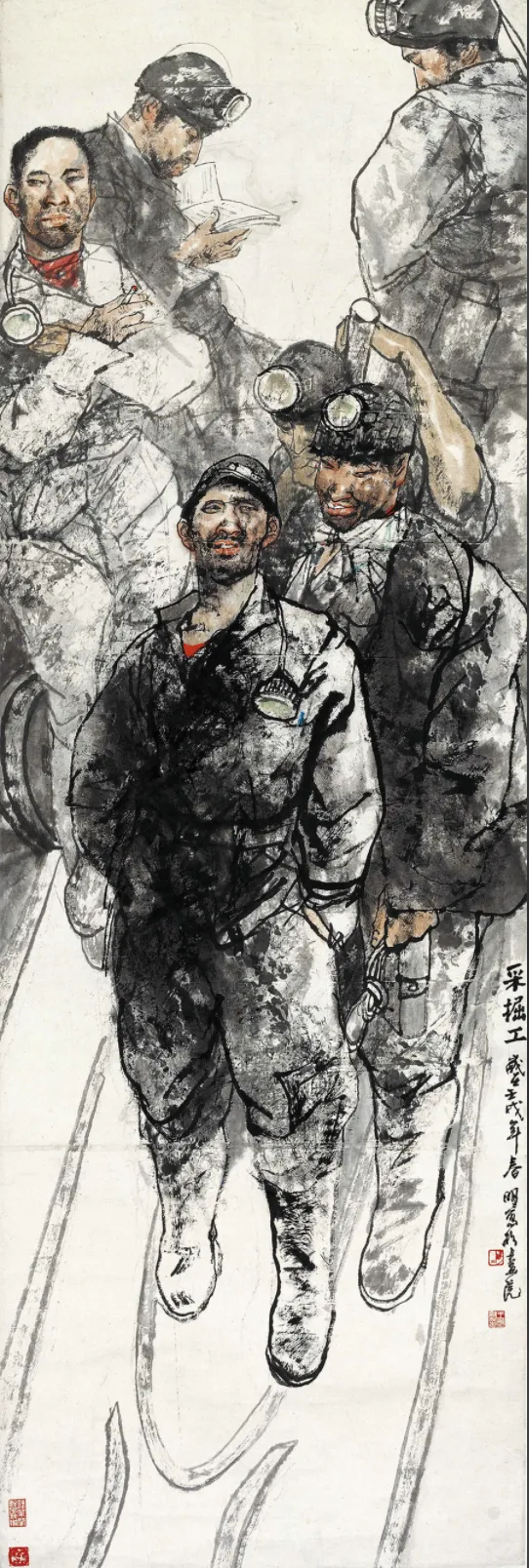

王氏以“能”闻世,兼顾人物、花鸟、山水,然人物画尤见其长。其所绘时装人物,常得秀丽婉约之致;古装人物,则显苍古雄浑之气。两者对映,其“能”于现实中磨砺,愈显深厚,而“逸”于古意中浸润,遂成雅趣。时装人物固磨其技,古装人物则写其神。因现实所限,明明遂辟古装题材,游心于古人生活,若豪放文士,临泉听涧,垂纶消夏,写七贤、屈子、东坡、诗圣,皆在不拘一格中流露“逸”之神采。为更显其胸中丘壑与时代风华,王明明旁采明代画法,妙用配景以增氛围,既与同时代画家区分,又融多艺于一炉,既能,又逸,风格自成,引领风潮,隐然有大家风范。

王明明之“逸”,非止题材之择,尤见笔墨之妙。其线条运笔,虽承古法,然于变幻中自得生动,时以铁丝之线,显现代意趣。明明虽崇传统,亦纳新法,笔墨间见传承与新生交融,成一派独具之风。其以“能”成“逸”,雅合文人之趣,复以“逸笔”携现代意境,开创“逸品”新姿。

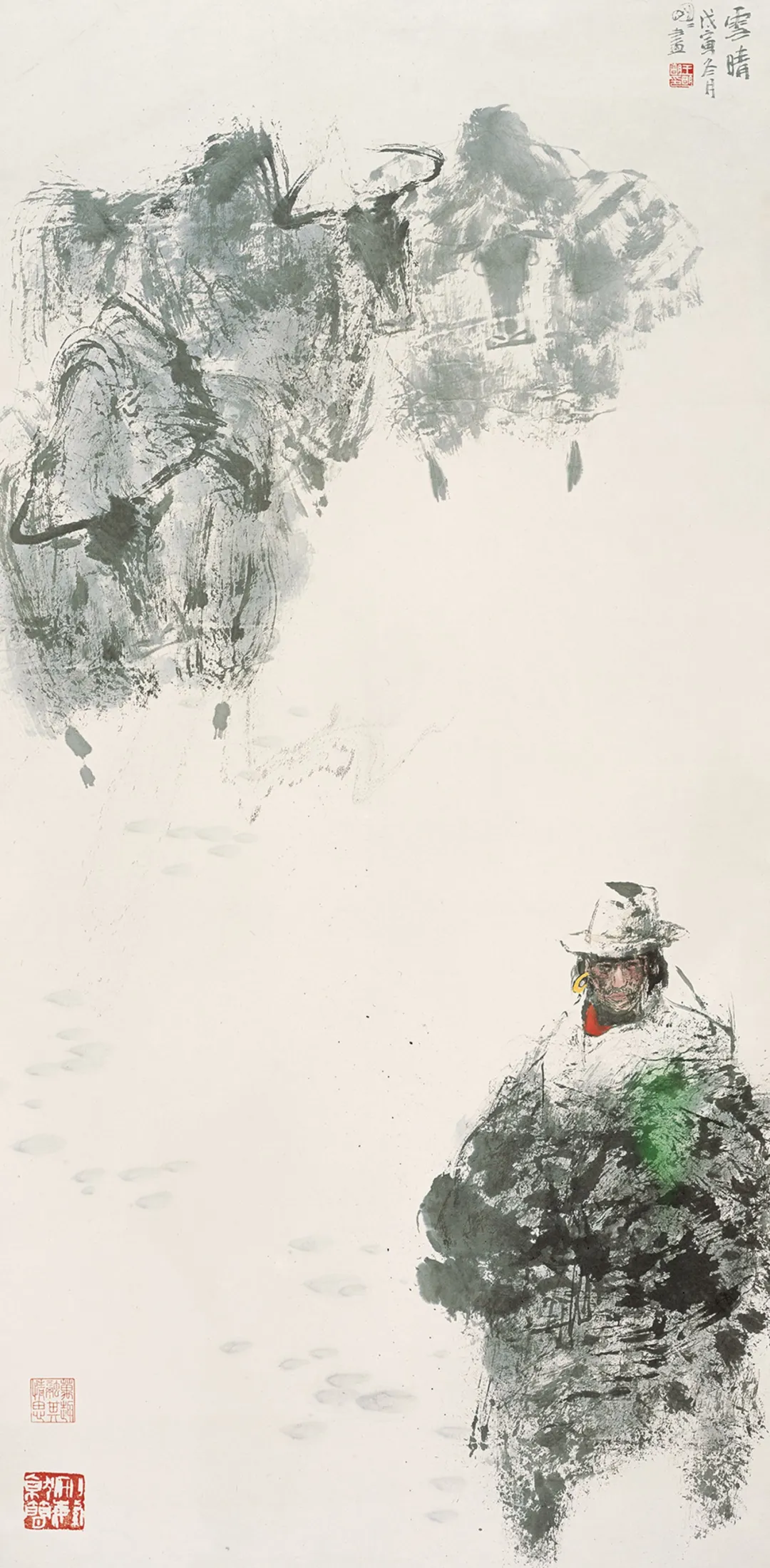

至于意境,王明明常追简劲灵动,作虽传神,然隐淡泊天真之旨。平淡者,境界也,非繁华可拟。古有禅宗老僧,初见山水如常,后悟非山非水,十年后复归山水本然,此乃返璞归真之道。天真者,绘艺至高,乃心性自然之流露。倪云林言“省笔见天真”,明明正得此意,笔随心行,不拘经营,于简逸中吐露空灵,蕴含画家真性情。其作不饰繁华,然于洒脱中自成意韵,凝结心绪,化为水墨之语,昭示超然之“逸趣”。

Wang Mingming: Reviving Tradition with a Modern Touch, Harmonizing Serenity with Subtle Elegance

Wang Mingming, born in 1952 in Beijing, hails from Penglai, Shandong. From a young age, he harbored a deep passion for art, with lofty aspirations. However, in 1969, at the age of seventeen, as the nation underwent significant changes, Wang Mingming was assigned to work as a machinist, wielding a metalworking tool daily. His arms were often weary, and his muscles strained, yet his determination remained unwavering. During breaks, he would take his drawing tools and venture into the countryside, capturing the essence of the landscape, and over time, his skills blossomed. After ten years in the factory, Wang Mingming’s heart was always set on painting, and he never ceased his studies. In 1978, feeling lost in his artistic journey, he turned to ancient themes, delving into the roots of Chinese culture to find his true path. He came to the realization that Chinese painting must follow traditional principles while embracing innovation to establish itself in the art world.

In 1977, under the recommendation of his mentor Zhou Sicong, Wang Mingming was admitted to the Beijing Art Academy, where he studied under various renowned artists. He mastered various forms, including figures, landscapes, flowers, birds, and calligraphy. However, his style became somewhat eclectic, lacking a clear direction. This prompted him to reflect deeply, seeking to break away from old conventions and create something new by blending traditional and modern elements to forge a new path in art. In 1980, he painted “Du Fu,” based on the poet’s “Spring View,” a historical figure painting that combined traditional techniques with new ideas, employing cinematic montage to juxtapose multiple figures within the composition, merging poetry with the painting’s ambiance. The following year, he created “Summoning the Soul,” depicting Qu Yuan by the Miluo River, where the ethereal mist and faint figures deepened the poetic and artistic resonance.

However, as the tides of reform swept through China, with Western influences seeping in, traditional painting methods were challenged, leaving many artists in a state of confusion. In 1983, Wang Mingming traveled to France, where he marveled at Western art. Yet, upon returning to China, he became even more convinced that Chinese painting must follow its own path and not be swayed by external trends. He thus became more resolute in exploring the essence of tradition, integrating modern thought to create poetic paintings that reflect his deep understanding of Chinese culture. From 1985 to 1989, Wang Mingming traveled extensively across China’s famous mountains and rivers, immersing himself in ancient and contemporary landscapes, which he then brought to life through his art. In 1989, he began creating a series of albums that encapsulate his decades of contemplation, merging poetry with painting, achieving a distinctive and mature style. In 1998, when hosting European museum directors, Wang Mingming showcased Chinese paintings, including works by Qi Baishi, leaving the European guests in awe. This experience deepened his understanding of the uniqueness of Chinese painting, emphasizing the need to preserve its essence and core. Chinese culture, with its profound history, must be deeply studied and integrated into the contemporary world to remain relevant and enduring.

In surveying Wang Mingming’s art, it is evident that he revives traditional styles within a modern context. His figures, flowers, birds, landscapes, and calligraphy all embody a spirit of clarity, expansiveness, and harmony. Upon first glance, his works exude an aura of purity and detachment from the mundane, encompassing a wide array of subjects, showcasing his extensive knowledge and foresight, as well as his independent character. Upon closer inspection, a sense of refined harmony emerges; his works are meticulous, devoid of the superficial, reflecting his disciplined nature. The harmony, in turn, reveals a sense of balance and a deep idealism. In sum, Wang Mingming’s art speaks directly to his true self, allowing Chinese painting to return to its traditional roots through his hands. His works not only cultivate the self and express emotions but also provide a means of contemplating the world, bringing him inner peace and joy through art.

Observing Wang Mingming’s paintings, one finds a mastery of technique (“ability”) that approaches the essence of “ease.” Traditionally, scholars revered “ease” and scorned “ability,” seeing “ease” as a gift from the heavens, unrefined by human hands. However, in today’s world, the winds of change have blown in, and relying solely on “ease” may prove difficult. Furthermore, those who truly understand “ease” are as rare as pandas. The concept of “easy strokes without concern for likeness” is one aspect of “ease,” but the crude brushwork criticized by Lu Xun does not necessarily fit into this category. Modern aesthetics emphasize “ability” without forsaking “ease,” though the meanings have evolved. Today’s connoisseurs seek skill that is neither mechanical nor vulgar but rather refined and close to “ease,” which is particularly esteemed.

Wang Mingming is renowned for his “ability,” excelling in figure painting as well as flowers, birds, and landscapes. His modern figure paintings are often delicate and graceful, while his ancient figures convey a sense of grandeur and solemnity. The contrast between the two highlights his “ability” honed through real-life practice, which deepens his mastery, while his immersion in ancient themes nurtures his “ease,” resulting in refined elegance. His modern figures refine his technique, while his ancient figures capture their spirit. Constrained by reality, Wang Mingming turned to ancient themes, immersing himself in the lives of the ancients, like a free-spirited scholar, listening to springs, fishing, or enjoying summer, depicting the Seven Sages, Qu Yuan, Su Dongpo, and the Poet Sage, all revealing a sense of “ease” without limitation. To better express his inner vision and contemporary spirit, Wang Mingming drew inspiration from Ming dynasty techniques, skillfully using backgrounds to enhance the atmosphere. This not only differentiates him from his contemporaries but also showcases a fusion of various techniques, creating a unique style that is both skilled and easy, subtly leading the way with the elegance of a master.

Wang Mingming’s “ease” is not merely in his choice of themes but is especially evident in his brushwork. His lines, while rooted in ancient techniques, gain vitality through subtle variations, sometimes using wire-like strokes to convey modern sensibilities. Though he respects tradition, he also embraces new methods, blending inheritance with innovation in his brushwork, creating a distinctive style. He uses his “ability” to achieve “ease,” aligning with scholarly tastes, and further, using “easy strokes” to convey modern aesthetics, thus creating a new form of “ease” in art.

As for creating atmosphere, Wang Mingming consistently pursues a style that is simple, powerful, and dynamic. His works, though vivid, subtly convey an essence of tranquility and innocence. Simplicity is a state of being, an ultimate realm beyond superficial splendor. An ancient Zen story speaks of an old monk who initially saw mountains as mountains and water as water; later, he no longer saw mountains as mountains or water as water, but after ten years, he once again saw mountains as mountains and water as water. This journey reflects the inevitable process of returning to essence, in line with the aesthetic principle that the most brilliant expression returns to simplicity. Innocence represents the highest aim in painting, the natural expression of the artist’s heart. As Ni Yunlin said, “Even with minimal brushstrokes, true innocence emerges.” Wang Mingming embodies this concept, letting his brush follow his heart, unrestrained by meticulous technique, revealing an ethereal quality in simplicity, reflecting the artist’s genuine nature. His works eschew elaborate decoration, yet within their freedom, they naturally form a unique rhythm, translating emotion and insight into the language of ink, embodying a transcendent sense of “ease.”

责任编辑:苗君