旭宇,讳许玉堂,号白阳、伯阳,字京东,己卯岁冬月生于玉田。幼承家风,诗书为乐,年方六龄,已喜吟咏古韵,意寄词章,沉潜其中。十余载间,临习颜体,心摹手追,渐悟达摩壁立之境,诗书造化于此潜移默运,根基日固。少时之功,经年累积,铸就日后文脉深厚。

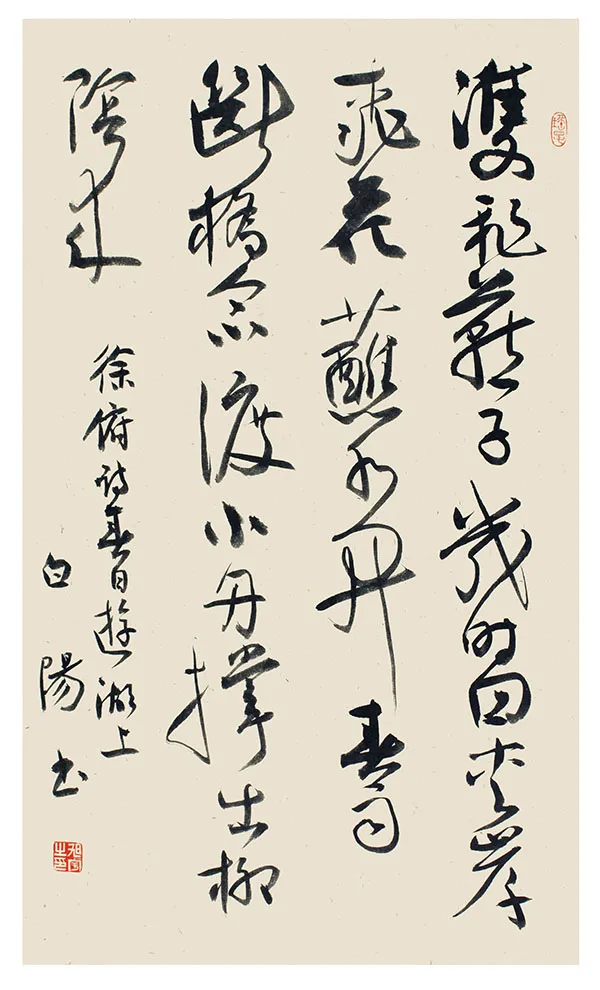

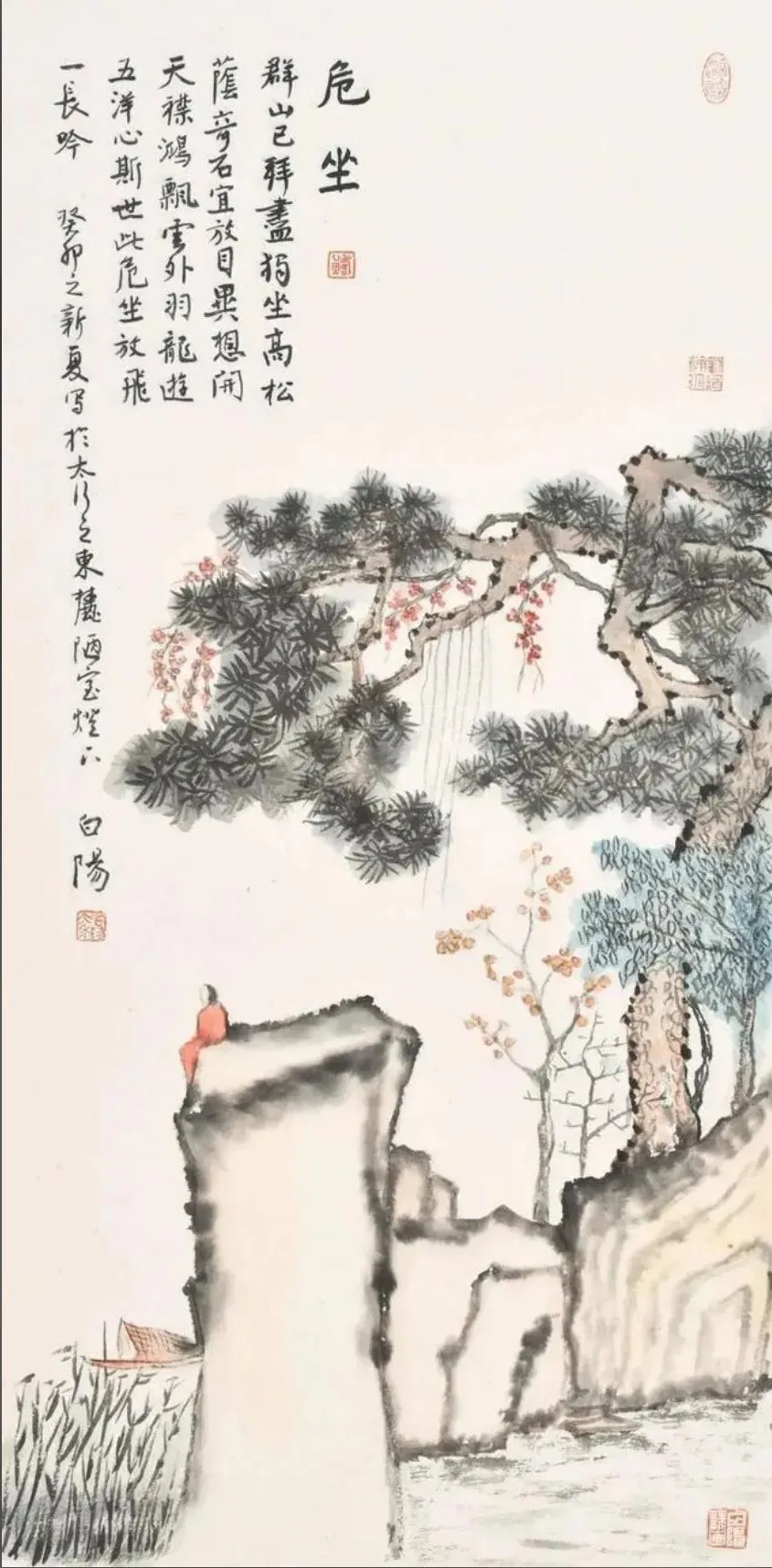

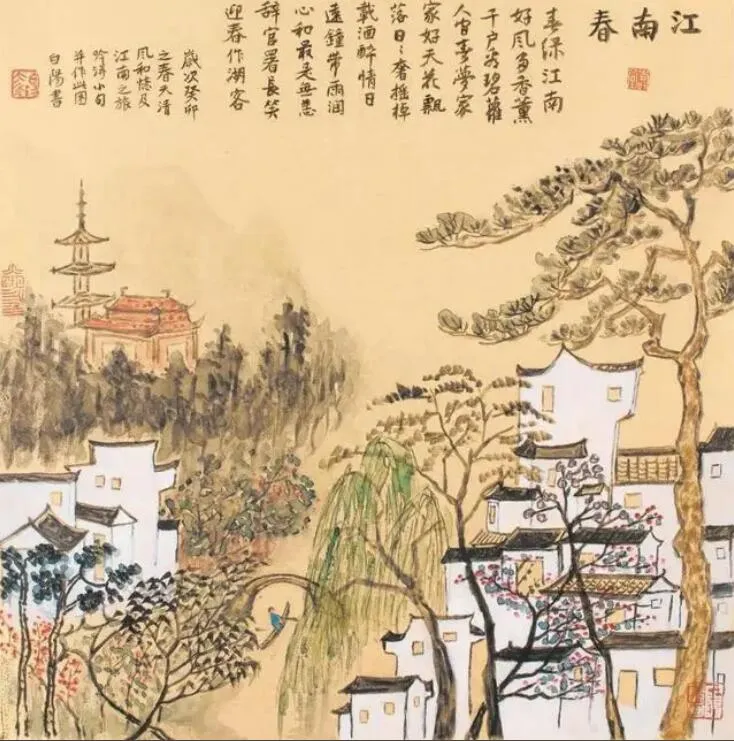

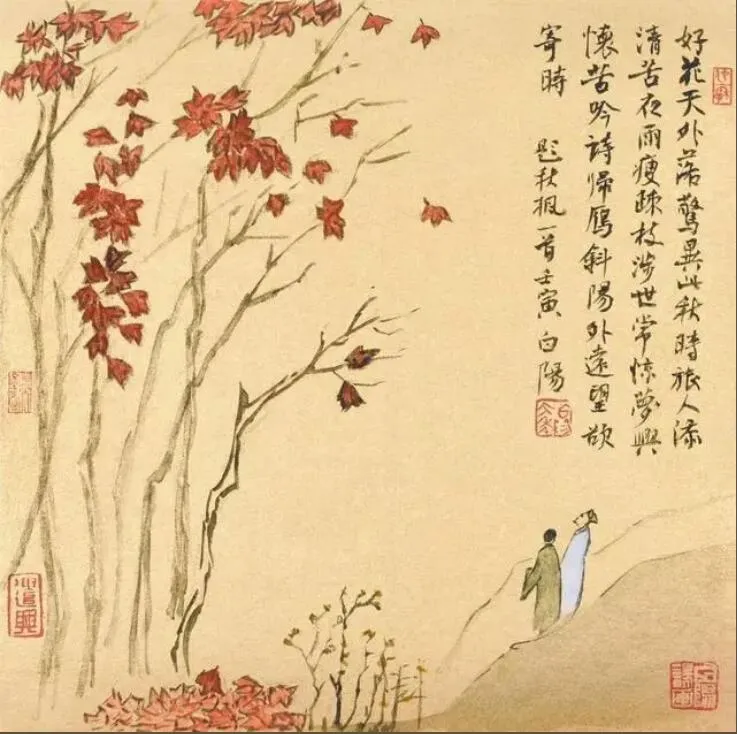

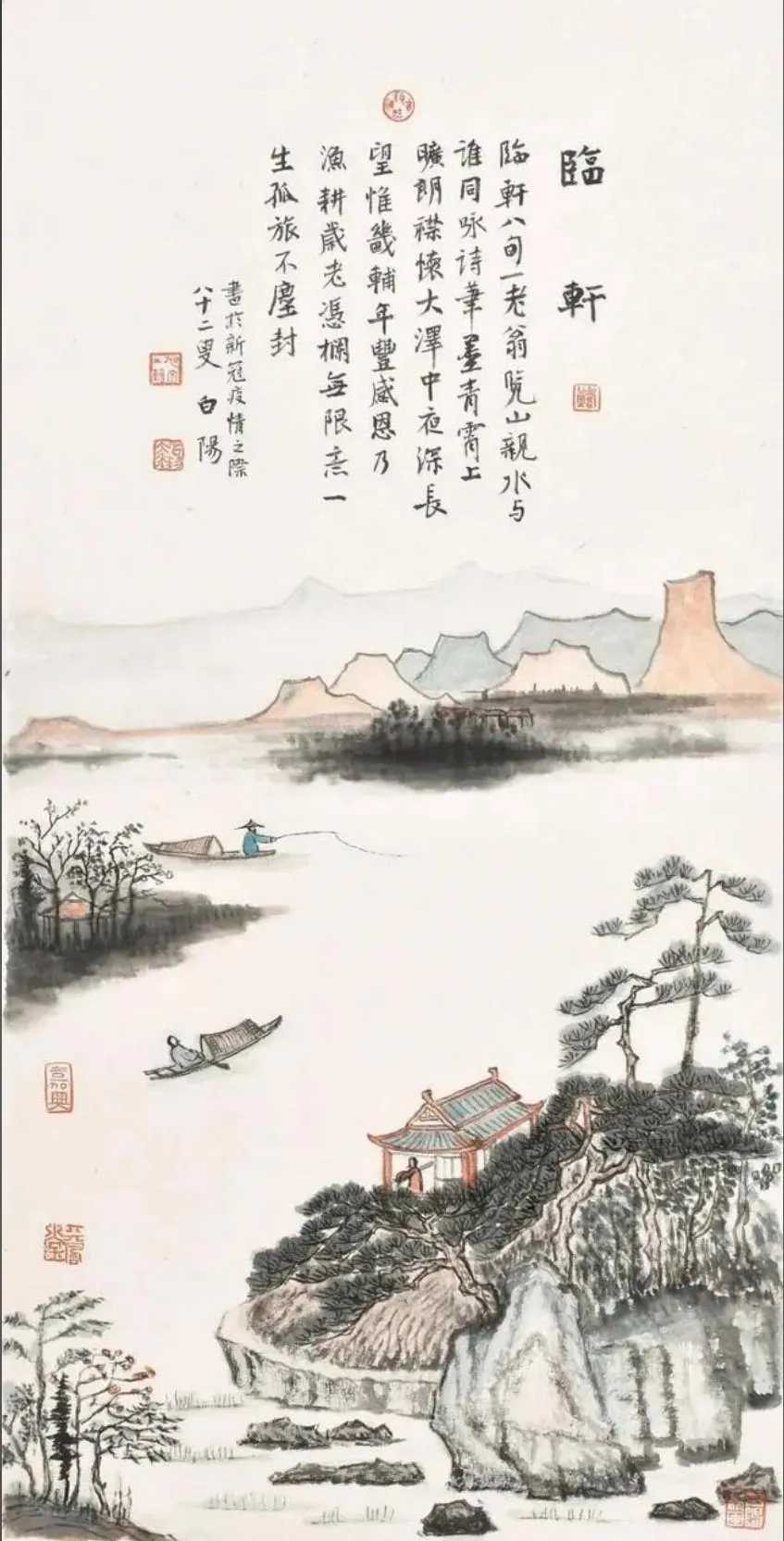

暮年,寄心山水,笔墨间流连自得。短短一载,涉足山川,初出之作,已获满堂彩誉。其笔意清远幽静,神韵自成,得益于幼时之修与岁月积淀。诗人气度,心境高远,作品意蕴深厚,流露出脱俗雅致之风,古雅浑然,卓然超群。

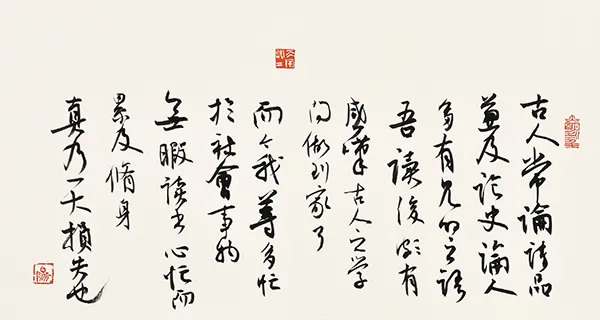

清人刘熙载有言:“书贵入神,然神分我他;入他神者,己化为古,入我神者,古融于己。”书圣王羲之亦道:“书者,玄妙之艺,非通达之人,难窥其奥。”黄庭坚则言:“学书必有道义于胸,兼广圣贤之学,方为上乘。”时人评旭宇书作,曰其书卷气盈,笔意洒脱而清丽,诗人之风,学者之韵,透纸而出,此正得益于旭宇积年修为,内外气质俱佳。

有人问及旭宇何以独钟宋元山水,先生淡然一笑,答曰:经年研习,始知宋元山水为文人画之本脉,意境高远,难以企及。晋唐山水,或简略未足;明清山水,逸笔草草,技法玩弄,反失其真。宋元之笔墨精微,意蕴绵长,最能传达文人画之精髓,故取法于此,以求至高之境。

自孔子之时,士人心怀天下,寄情山水。“浴乎沂,风乎舞雩,咏而归”,“仁者乐山,智者乐水”皆为高士之志趣。魏晋时,竹林七贤啸傲山林,王羲之流觞曲水,山水画随之肇兴。南朝宗炳《画山水序》云“竖画三寸,当千仞之高;横墨数尺,体百里之迥”,倡“澄怀味像”,以图畅神。唐张彦远言“拟迹巢由,放情林壑,纵烟霞而独往”,山水画遂为文人修养之道。王维咏山水,悟禅意,倡“诗中有画,画中有诗”。

至宋,苏轼以墨竹枯木抒怀,言“文以达心,画以适意”,“莫若书与画”,文人画成为士人逸兴。元吴镇云:“词翰之外,士人画兴,适一时之意。”旭宇承此风骨,晚岁尤醉心山水,书法沉潜古韵,清逸幽远,山水画中融通天地,笔意高迈。其每临古迹,常感澄怀畅神,山川入胸,万象入笔,自言唯山水能悟胸中之境,于笔墨中契合自然,追求大美之道。

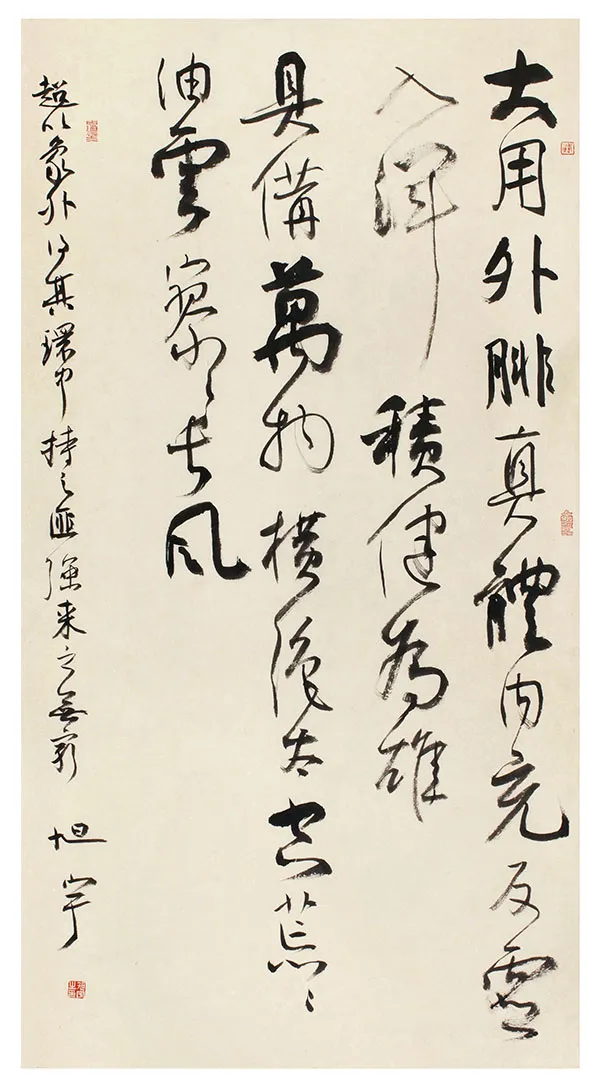

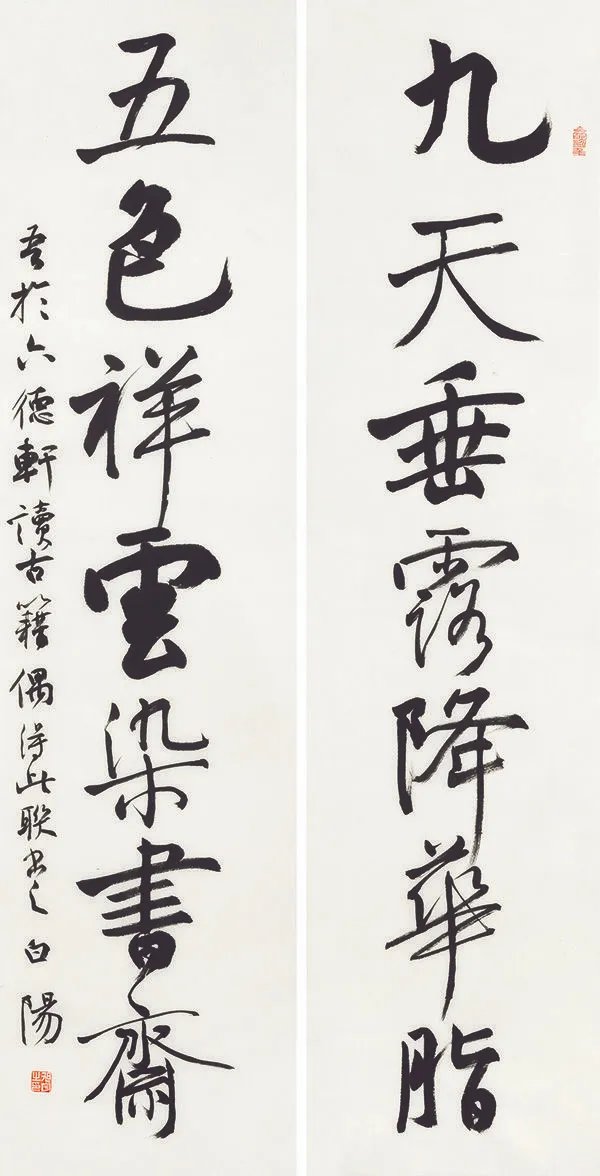

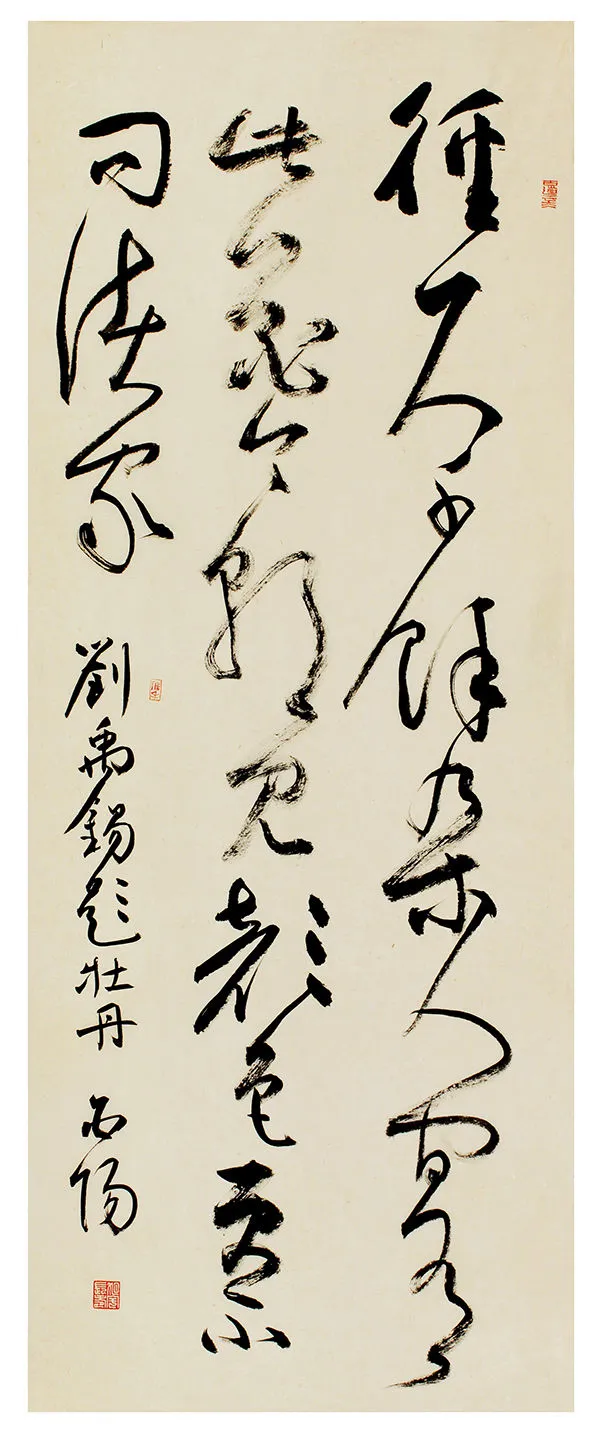

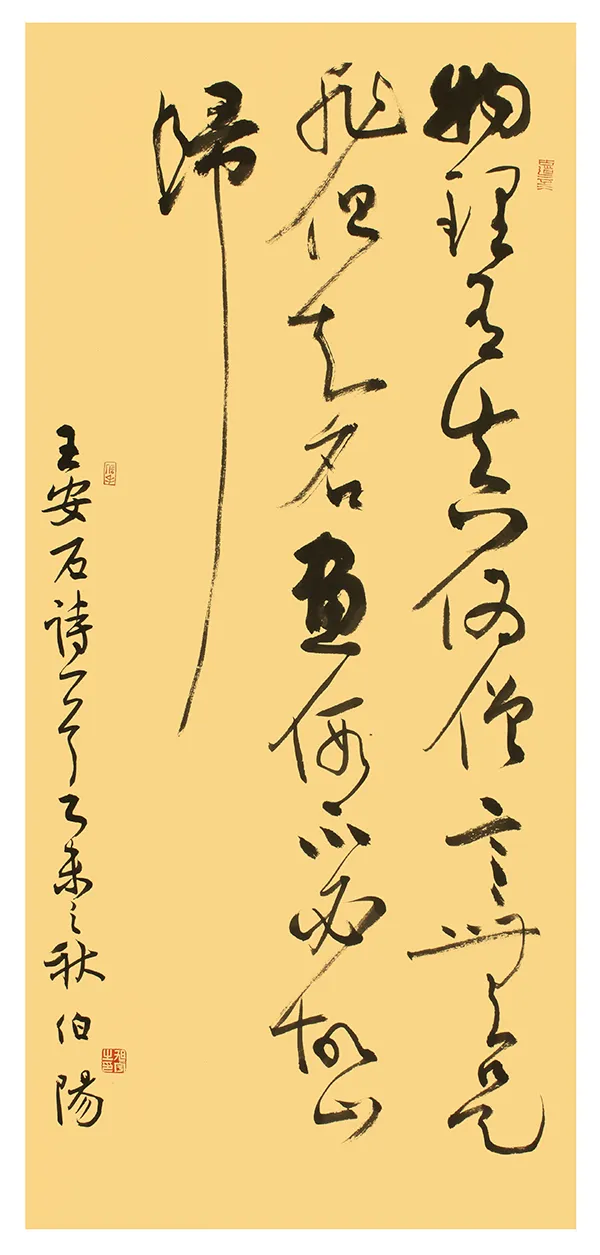

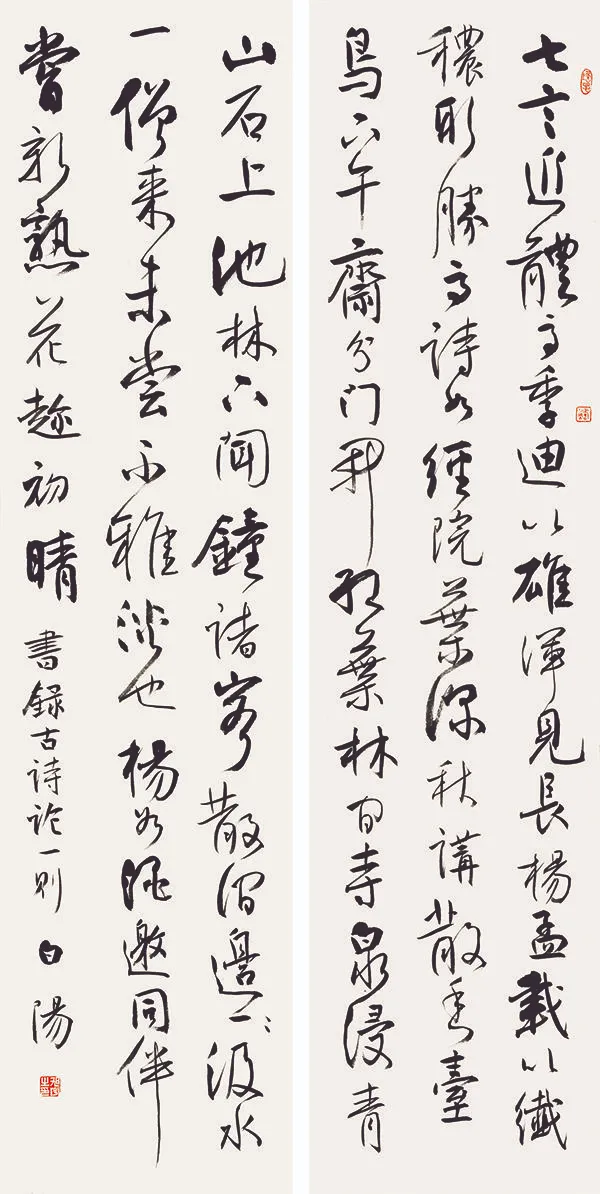

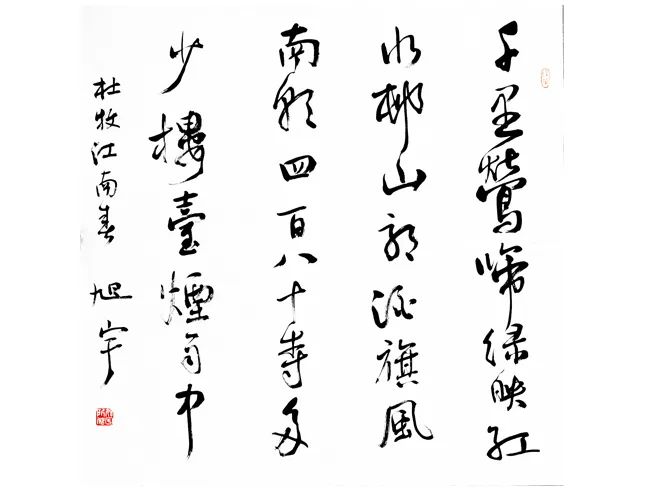

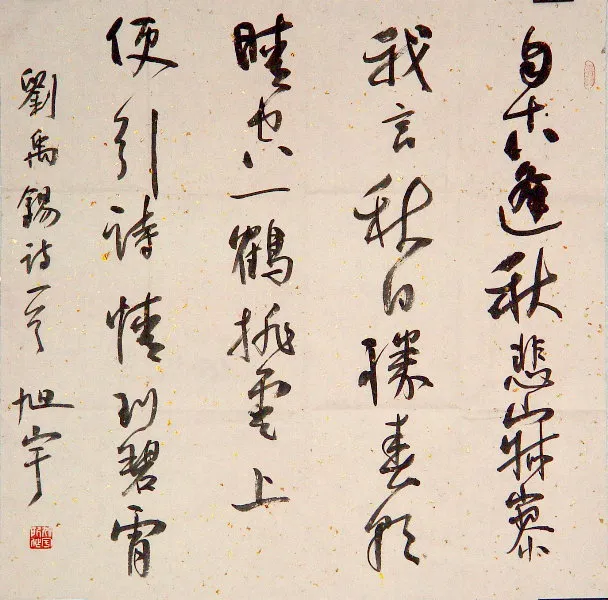

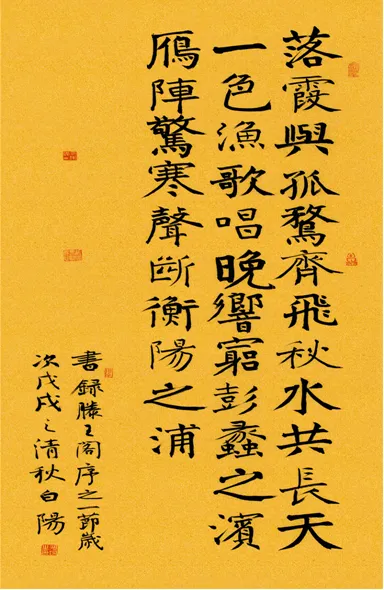

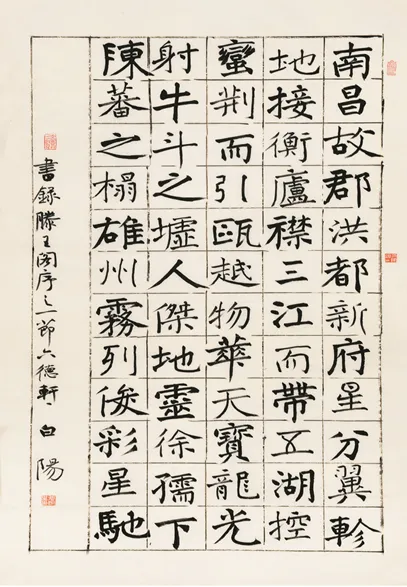

旭宇倡兰亭之风,躬行践履,专注“今楷”之道,研创并进,成果斐然。其“今楷”以方笔为主,笔力遒劲,碑骨与帖韵并蓄,线条饱满,沉稳雄浑,独具风采。首露锋芒,便得赞誉四起,博得广泛认可。除“今楷”外,旭宇于行草尤见功力,深悟“二王”神髓,运笔老辣生动,行间流畅自如,毫无滞碍,满纸灵光,意境高远。方家评其行草,称其独具风骨,妙韵隽永,真可谓人书俱老。

旭宇书法,不止技艺,更是品性涵养之积淀。其学养深厚,才情卓然,思理明达,皆寓于笔墨之中。及退隐书斋,八十五岁高龄,仍焕发勃然生机,潜心文化研习与书画创作。其书,无论“今楷”或行草,皆能予人以审美之乐,雅趣盎然,乃其数十载耕耘传统文化之结晶。此真老子所谓“大器晚成”者焉。

画变法,古今多见,然至衰年而拓新境者,尤为难得。齐白石五十五岁进京,初作寂寂,后改笔创新,遂为一代巨擘。至八十八岁,尝题画云:“年添一岁,八十八矣,旧笔去否?”言其老而不倦,志在变通。黄宾虹六十而后,焦墨淡墨并施,枯润交融,开山水新意。林散之六十岁始专草书,终成草圣。旭宇名振诗书四五十年,至去岁,忽醉心山水,八秩之年复拓新境,承古文人雅意,立于当代,诚为艺林奇观。

旭宇年逾耄耋,心境澹泊,研习传统文化与书画妙理,潜心笔墨,追宋元之韵,合时代之气。于数十载诗书学养之基,再开新境,拓艺海广阔,成就文人艺术新篇,观者无不倾心仰止。

Xu Yu: Subtle Shifts in Brushwork, Serenity and Profound Rhythm

Xu Yu, whose given name is Xu Yutang, styled Baiyang and Boyang, with the courtesy name Jingtong, was born in the winter month of the ji-mao year in Yutian. From an early age, he was immersed in the family tradition, finding joy in poetry and calligraphy. At the age of six, he was already fond of chanting ancient verses, deeply immersed in their refined charm. Over a decade, he diligently studied Yan style calligraphy, gradually gaining insight into the profound essence of the art, much like Bodhidharma contemplating the wall. The foundation laid in his youth, nurtured by years of accumulation, shaped the deep cultural heritage that would characterize his later achievements.

In his later years, Xu Yu turned his heart toward landscapes, finding solace in the flow of ink and brush. Within a short span of one year, he ventured into landscape painting, and his debut works quickly garnered widespread acclaim. His brushwork, serene and distant, radiated a unique charm, a testament to the artistic discipline nurtured in his early years. His poet’s temperament and elevated mindset endowed his works with profound meaning, exuding an air of refined detachment, resonant with an ancient elegance and a peerless style.

As Liu Xizai of the Qing dynasty once remarked, "Calligraphy excels when it enters the realm of the divine, yet the divine may differ between self and others; when one enters the divine of others, the self is absorbed into the ancients; but when one enters one's own divine, the ancients become absorbed into the self." Likewise, the calligraphy sage Wang Xizhi said, "Calligraphy is a profound art, one that cannot be fully grasped by those who lack deep insight." Huang Tingjian of the Song dynasty also noted, "To learn calligraphy, one must have moral integrity in the heart, coupled with the broad learning of sages and philosophers—only then can calligraphy be truly valued." Critics of Xu Yu’s calligraphy have commented that his works overflow with a unique cultural air, his brushstrokes being both graceful and free, exuding the spirit of a poet and the scholarly charm of a learned man, a reflection of Xu Yu’s deep cultivation and distinctive character.

When asked why he favored the landscapes of the Song and Yuan dynasties over the tradition of landscape painting from the Jin and Tang through to the Ming and Qing dynasties, Xu Yu would smile and explain: through years of research, he discovered that Song and Yuan landscapes not only formed the root of literati painting but also represented the zenith of its aesthetic realm. The landscapes of the Jin and Tang dynasties, though pioneering, appeared somewhat simplistic; those of the Ming and Qing, while adept in brush techniques, often became overly playful and careless. Song and Yuan landscapes, with their intricate brushwork and profound artistic conception, most accurately conveyed the essence of literati painting. Therefore, he chose to study these works in his pursuit of the highest artistic realm.

Since the time of Confucius, scholars have harbored both a concern for the world and a connection with nature. "Bathe in the Yi River, feel the breeze at the dance platform, chant as you return home," and "The benevolent find joy in mountains, the wise delight in water" reflect the aspirations of ancient scholars. During the Wei and Jin dynasties, the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove reveled in the natural world, while Wang Xizhi hosted the famous literary gathering by the Lanting stream, where landscape painting began to flourish. Zong Bing of the Southern Dynasties, in his "Preface to Landscape Painting," wrote, "A painting three inches high may express the grandeur of a thousand-foot peak; a few feet of ink may capture the expanse of a hundred miles," advocating for the spiritual cultivation through landscapes. Zhang Yanyuan of the Tang dynasty said, "Following the footprints of Recluse Chao and Sage You, one may find joy in the forest and valley, in harmony with the zither and wine, freely wandering through mists and clouds." Thus, landscape painting became a means of scholarly self-cultivation. Wang Wei not only praised landscapes in poetry but also grasped their spiritual and Zen-like essence, promoting the ideal of "poetry within painting, painting within poetry."

By the Song dynasty, Su Shi expressed his sentiments through ink bamboo and withered trees, saying, "Literature expresses my heart, painting fulfills my desires," and "Nothing brings greater pleasure, yet fails to move one's soul as deeply as calligraphy and painting." Literati painting thus became the chosen artistic pursuit of scholars. Wu Zhen of the Yuan dynasty remarked, "Beyond poetry and prose, painting serves as a diversion for scholars, satisfying their immediate interests." Xu Yu inherited this spirit, and in his later years, became deeply enamored with landscapes. His calligraphy, steeped in ancient rhythm, exudes a quiet elegance, while his landscape paintings harmonize heaven and earth, with brushstrokes of grandeur. Each time he studied ancient works, he found deep spiritual solace, his heart filled with mountains and rivers, and all phenomena captured by his brush. He often said that only through landscapes could one truly comprehend the inner realm, finding resonance between brush and nature, striving toward the ultimate beauty.

Xu Yu championed the spirit of the Lanting gathering, practicing and advocating for it. He dedicated himself to the creation of "modern regular script," advancing it through rigorous exploration and innovation, yielding remarkable results. His "modern regular script" is characterized by square strokes, vigorous brushwork, and a blend of the monumentality of steles and the fluid elegance of running script, creating lines that are full, powerful, and imposing, while also exhibiting a new vitality. Upon public exhibition, it was immediately met with widespread acclaim. In addition to his achievements in "modern regular script," Xu Yu is also highly skilled in running cursive, deeply absorbing the spirit of the "Two Wangs." Critics have noted that Xu Yu’s running cursive is highly distinctive and rich in charm, exemplifying a mature mastery, with brushstrokes both seasoned and dynamic, flowing naturally with no trace of hesitation, each line radiant with traditional brilliance, reaching lofty artistic heights.

Xu Yu’s calligraphy is not merely an artistic skill but also a reflection of his moral cultivation. His works embody his profound scholarship, extraordinary talent, philosophical insight, and open-minded thinking, all conveyed through his brushwork. After retiring, even at the venerable age of eighty-five, Xu Yu continued to radiate youthful energy, immersing himself in cultural research and calligraphic creation. Whether in "modern regular script" or running cursive, his calligraphy provides viewers with aesthetic pleasure and delight, reflecting his decades-long dedication to preserving and inheriting China’s rich cultural heritage. This is truly what Laozi meant by "a great vessel is late in becoming."

The phenomenon of innovation in the twilight years of an artist's life is not uncommon, but it is particularly remarkable. Qi Baishi, after moving to Beijing at the age of fifty-five, initially found little recognition for his work, but later innovated his brush technique and became a great master. At eighty-eight, he once inscribed on a painting, "Another year has passed, now I am eighty-eight. Have my brushstrokes changed from the old ways?" expressing his lifelong pursuit of change. Huang Binhong, between the ages of sixty and eighty, developed a new approach to landscape painting, blending dry and wet ink, opening a new chapter in the art of landscape painting. Lin Sanzhi, after the age of sixty, devoted himself to cursive script, becoming a revered master of the form. Xu Yu, renowned for his poetry and calligraphy for forty or fifty years, suddenly, in the past year, became deeply enamored with landscape painting. In his eighties, he once again broke new ground, inheriting the spirit of traditional literati art and standing as a unique figure in contemporary art.

At over eighty years old, Xu Yu maintained a serene state of mind, immersing himself in the study of traditional culture and the mysteries of Chinese calligraphy and painting. With a heart devoted to brush and ink, he drew upon the essence of the Song and Yuan dynasties while integrating the spirit of the times. Building upon his decades of poetic and scholarly foundation, he opened new realms of artistic expression, expanding the horizons of literati art and inspiring admiration from all who beheld his works.

责任编辑:苗君